(Okay, not really…but close.)

There’s a whole lot of pre-amble and follow-up that should accompany this, but being linearly- challenged as I am, it will wander along in its own chaotic way.

* * * *

Since mid-2008, there had been some discussions about having DARC (Dark Ages Re-Creation Company, http://darkcompany.ca ) go out to L’Anse aux Meadows, Nfld, to do a presentation at the historic site. 2010 is the 50th anniversary of the site, and it was decided that a series of special events would occur throughout the season, and we were invited there in August of this year for ten days.

Conversations with Dr. Birgitta Wallace, the site archaeologist, suggested a scenario of a boat going from Iceland to Greenland, getting off course, and ending up joining up temporarily with the crews already at L’Anse aux Meadows / Leifsbuðir. This meant we spent the year and a half fine-tuning and adjusting our gear to fit more specifically into a defined timeframe and locale, than we normally worry about.

It also meant I needed to start looking into foodstuffs of Iceland, circa 1000 AD.

Until this point, I’ve mostly done as others have done, accumulated a larger list of foods appropriate to the Viking Age, and the entire Norse world. Even that range of information is limiting. I’d had no idea beforehand how much more restricted a list of Icelandic foodstuffs would be!

I started by searching out as much info as I could, and it wasn’t till I began that I realized just how unspecific the usual sources were. Or how much overlap. Or how vague. Even in the current world of the internet, which at least opens up some new vistas, it appears to either be a case of ‘neat thing if it were actually written up/translated/available’, or ‘gee, same source quoted over and over again’. It was even scary to find odd vague things that I’ve said myself somewhere, usually in the dim dark past, were popping up as reasons why someone else believed something to be true! Ack!

(I suppose that’s one of the reasons why I’m so slow to ever make a statement or publish something; knowing I don’t have every fact available, and worrying that the next new bit of info will make whatever I just said obsolete.)

On the other hand, I am always truly thankful to anyone who, at the very least, talks out loud about his or her experiments. It’s that combined, if remote, brainstorming that can sometimes open a door…

I did turn to a friendly archaeologist who has done a fair bit of work in Iceland, and picked his brains more than just a bit. That’s about when the slim list of ingredients started to become an almost non-existent list! It seems that there’s not much by way of indigenous foodstuffs in Iceland. No land mammals, no fruits other than a few berries. So, fish, sea mammals and sea birds, blueberry and crowberry, and mushrooms.

The geography doesn’t allow for natural basins of salt, the temperature is too chill for evaporation, and there was quickly a shortage of fuel, which made other methods of salt production impractical. That would mean that methods of preservation would be reduced to drying or pickling in whey, with only minimal brining, or smoking, more by luck than by intent.

Arable land was used for growing fodder for herd beasts, and less for crops. Some grains were grown, though likely used in the production of beer. Certainly, I’m told there was no evidence of bread-making tools, querns or baking plates, until later. And dentition records imply no sugars in the diet until the post-Medieval period. (And no honeybees so no honey; even less possible sugar in the diet.) Apparently this sort of dentition evidence is peculiar to Iceland.

While this suggests a diet consisting of dairy products and meat and fish, which is not necessarily a meagre diet, it also wasn’t a good basis for pre-packing.

I needed us to be relatively self-sufficient. I’d had an offer from friends to provide us with some local availabilities information, but I assumed (correctly) that there’d be less than no time to go search for foodstuffs once we were there. I put some feelers out with other members of the team to keep their eyes open for some other sources of seaweed/dulse, and they also came across some other cheese and dried meat on their routes to the Northern Peninsula.

But primarily I needed to prep what I could ahead of time, sticking as closely as I could to what would have been likely foodstuffs.

Back in 1996, in the original demonstration of the interpretive program, there had been several other factors in play, which made it simpler.

- There were fewer of us. 4 interpreters from Ontario, and 4 local volunteers.

- There was less information easily available, so working with appropriate technology and avoiding modern ingredients was far simpler than trying to use only locale-specific ingredients.

- I had easy access to the staff kitchen at the visitors center, for clean up and storage. (This year the visitors’ center was still under reconstruction.)

- Water was more easily accessible. (I know this has to be a lie, since we carried drinking water from the VC in 1996, same as we’d started this year, and the VC hasn’t moved, neither had the reconstructed buildings. So perhaps it’s the intervention of 14 years? Not to mention that we needed water for 16 this time around…)

- There were fewer visitors in 1996. (Now it was always a goal that attendance would increase, and I think it’s a credit to the interpretive program that this has happened, but it meant that this time they really weren’t many non-public moments to attend to mundane basics of food prep.)

- In 1996 the fires we used were all real wood fires. Since then, because of smoke problems, the buildings have been fitted out with propane fires. This year I was alternatively cooking outside on the gate yard fire pit (which was far less pitlike, and could have used a bit of tweaking) or in the blacksmith’s house on his charcoal work fire.

- In 1996, it was still the heyday of public involvement in foodways programs. I was able to make flatbreads and share them out. A few very interested patrons could stay for a bowl of soup… Nowadays, when the public aren’t allowed to sample, I end up feeling somewhat inhospitable if I’m spending too much time paying close attention to food they’re only allowed to look at. And that could just be me and my feelings.

But I did want to find a way to simplify the process of feeding the team, while incorporating it into the overall aim of the program.

My plan was to prepack ‘Viking Cup-o-soup’ packets, so that each day we really only had to sort out the day's allotment of bits, and go. It was not a bad idea, and it really kept daily prep to a minimum.

It wasn't, perhaps, as much fun, or as much a ‘demonstration’ as chopping things up in front of visitors, and discussing ingredients as you go, but starting at 10am, after the visitors' day had already begun, and the difficulties involved in fetching water for clean up, as well as trying to not show too many modern foodstuffs, made it the wiser course

I'd ended up compromising on a list of foods. I'm sure the Norse at LAM would have been eating a lot of fresh fish or meat from sea mammals. And while, in the long run, our hosts graciously brought us a number of treats, I didn't want to rely on that possibility. So I'd planned our soups to use salted, dried fish, or dried beef. And because I wanted that to stretch a little further, I had also dried some onions and vegetables, and added seaweed and grains into the mix.

I also dried several roasts of meat into jerky, and made flatbreads (even if evidence of grain usage in Iceland is sketchy). After some experiments, I had decided to take along a number of blister packed cheeses which I brined as days went on, to more resemble young fresh cheese. (The new interpretation at LAM allows for some herd beasts off foraging...)

Once again, probably catering to our modern sensibilities, rather than those of the Norse, I attempted to make each soup packet very slightly different. (In 1996, these thoughts hadn’t even crossed my mind. I had dried fish to go in the soup, and all of the same ingredients each day. Variety occurred when the Parks Canada staff offered me a different ingredient. We had caribou one day, seal another. But beyond that, it was fish, fish, and fish.)

But I’m guessing that cooking for larger groups of people over the years, in an atmosphere of catering to needs and tastes, has made me awkwardly hyper-conscious, especially in a setting where alternatives are few and far between!

So, in preparation for the adventure I continued my regular drying of mushrooms, (I’ve been drying mushrooms for years, after having discovered how easy it is, and how useful they are) and to these I added onion, leek, and chive. Since every spring I harvest wild leeks, this year I also dried those in anticipation of the trip.

Because I could find mention of wild parsnip and wild carrot in some of the nearby countries, I decided to boldly risk the inclusion of their domestic counterparts, though I shredded and dried them, and overall it was a fairly minor ingredient. The inclusion of seaweed was a given, both for a useful green, and for its salt content and iodine.

I pondered a while about the inclusion of grains, since the archaeological evidence suggests they did not make up much of the Icelandic diet. But some kind of flatbread filled a gap in a lunch, where I couldn’t necessarily guarantee more dairy or meat, and grains in a soup make it heartier. It also seemed a more likely way of cooking a few grains, if there wasn’t evidence of flour-making or baking tools. I did try to limit myself to whole kernels of less modern grains.

In the flatbreads that I made ahead, or each morning, I was also using oat, barley, and spelt flours, with just a small bit of whole wheat to bulk it out. They were made using just flour, water, and a little salt; except for the ones I made our last day that used up some leftover blueberries!

Overall, except for the need to feed a large group of people at a specific time, when they had tasks that kept them busy at their own stations, or possibly trying to cater to some less-experienced or adventurous tastes, and the requirement that it all be packed along with us for the days it took to drive to Newfoundland, and the ten days of the presentation, I think it wasn’t an outrageously incorrect menu.

Certainly it worked, and none of us appear to have starved. I didn’t get the opportunity to play around with any of the experiments I’d had faint ideas of, or look into some of the local ingredients I’d been interested in, but then there’s often more I want to try that just doesn’t fit into the time allowed. I’ll just have to treat this as a starting point, and explore further.

- vandy

[crossposted from Dagda's Cauldron]

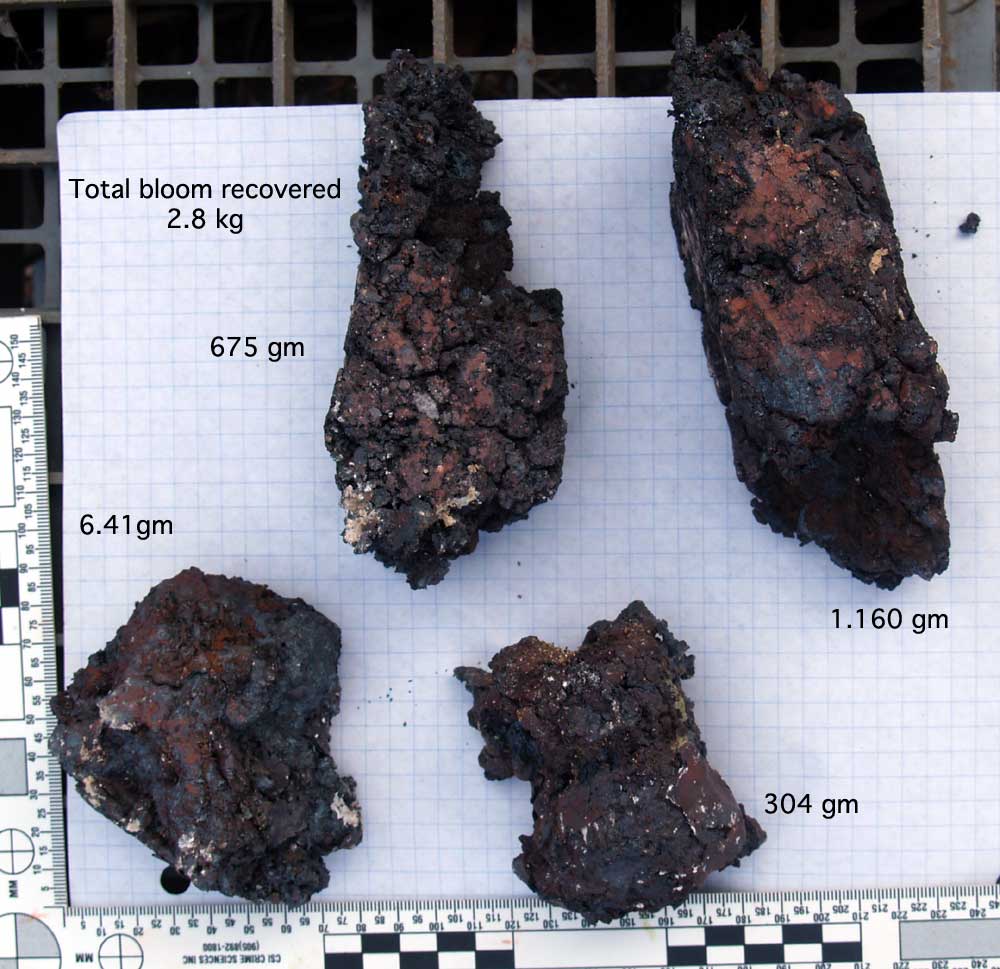

The assembled team, after the smelt.

The assembled team, after the smelt. This is the equipment set up, seen the evening before the smelt.

This is the equipment set up, seen the evening before the smelt.